In 1989, I moved from Vienna to New York City. My mother gave me a copy of Josef von Eichendorff’s “Memoirs of a Good-for-Nothing” (1826) on the way – guess why…. The book contained seven lithographs. It became one of my favourite books, just like Voltaire’s Candide and Italo Calvino’s The Baron in the Trees.

Scroll down for German version.

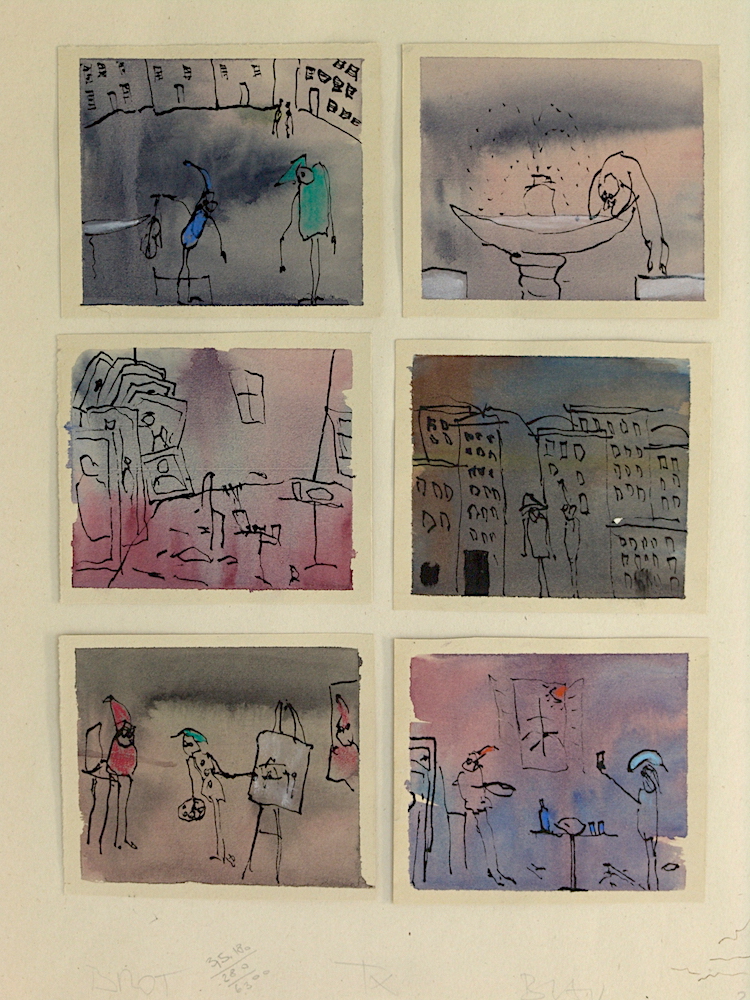

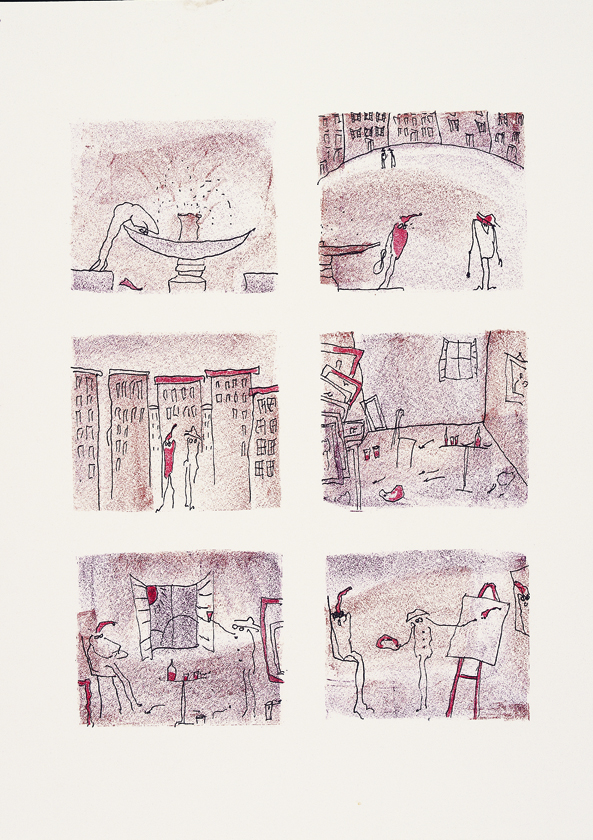

For me, seven illustrations seemed a tad few and so the idea arose to illustrate the book throughout. I decided to create so many illustrations that it would theoretically no longer be necessary to read the book. Like a movie. More than 300 water color drawings came into existence. An offset reproduction did not seem very appealing to me so I set out to search for a lithograph-workshop.

I discovered a printing workshop in Hungary (before the fall of the Iron Curtain) where i worked for an entire summer. Along with it came the best printers Eastern Europe had to offer and the stones I worked on were the same that Toulouse Lautrec had worked on a century before me – by winds of fortune they had ended up in Hungary. Wonderfully skilled and devoted printers helped me realise the project. I drew 210 images on the stone – and for each picture five different layers.

The book works like a film – frame by frame. One could call this book my FIRST MOVIE.

In some drawings I zoom into the action described by Eichendorff, others function like master shots. In some cases a lithograph image covers a paragraph of the book, others translate an individual sentences only. As a result one can read the book without having to read it. If one is not familiar with Eichendorff’s novel one can follow the plot by looking at the pictures only.

The ‘good-for-nothing’ lives in a different order. A charming rebel, who does not defy the generally accepted life picture by appearance or rough characteristics, but through his deeds subtly calls to attention that a life full of love and passion is a greater source of happiness than security and filthy lucre. Les affair, a big piece of starry-eyedness and naiveté cause him to get into all kinds of precarious situations. Fate properly engulfs him, throwing him to and fro like a speck of dust, and he, light as a feather, seems to go wherever the wind blows him. He slightly resembles Voltaire’s CANDIDE, but is, nevertheless, born under a luckier star, which spares him all of the sorrow of this world. Accordingly, he does not need to arise from the ashes like CANDIDE and PHOENIX do, instead, he considers his minor misfortune bad enough to be always on the run. On the other hand, he has what Friedrich Schlegel once called – freely quoted: ‘the only divine element humans bestow – that is idleness.’ He cannot be surprised by conventions and even if it hurts him that he is not “part of,” he is, after all, pretty content that do’s and dont’s are all up to him. And the ‘good-for-nothing” is not at all lazy. Egon Friedell wrote in 1931: “While Weber would even in times of direness and obscurity always remain the Baron and Gentleman, Schubert was his whole life long like Eichendorff’s ‘good-for-nothing’, the lazy Hans from the village, who happily traded his freedom for poverty. And like the ‘good-for-nothing’, he was not lazy at all, but very diligent, even without being aware of it: By singing all the time, half a thousand songs.”

if you interested in the book please click here or contact eh@akis.at

1989 zog ich von Wien nach New York. Meine Mutter gab mir Josef von Eichendorffs „Aus dem Leben eines Taugenichts“ (1826) mit auf den Weg, illustriert mit sieben Lithographien. Sieben Illustrationen fand ich etwas dünn und so kam die Idee das Buch durchgehend zu bebildern. Ich entschloss mich so viele Illustrationen schaffen, dass es nicht mehr notwendig sein würde, das Buch zu lesen. Mehr als 300 Aquarelle entstanden. Als Vervielfältigungsmethode wählte ich die Lithographie – ein original Druckverfahren.

Bei meiner Suche nach einer qualifizierten Druckerei stieß ich auf VAC, Ungarn, das damals einen Lithographiewerkstätte beherbergte, mit den besten Druckern, die Ost -Europa zu bieten hatte. Einen Sommer lang malte ich basierend auf den Aquarellen 210 Bilder in fünf Farben auf die Steine von Mühely Orszagos Grafikai, jene Steine die schon Toulouse Lautrec verwendet hatte. Ein Zufall hatte sie nach Ungarn “geweht”.

Es entstand ein Buch das funktioniert wie ein Film bestehend aus Standbildern. Man Könnte es als meinen ersten Film bezeichnen. Manchmal gehe ich in der Zeichnung einem Zoom gleich ganz nahe an das Geschehen heran, dann wieder zeige ich einen Überblick. Jedem Absatz, manchmal einzelnen Sätzen ist jeweils eine Lithographie zugeordnet. Man kann das Buch lesen ohne es zu lesen. Auch wenn man den „Taugenichts“ nicht gut kennt, kann man ohne Schwierigkeiten dem Verlauf der Geschichte in Bildern folgen.

Der „Taugenichts“ lebt in einer anderen Ordnung: Ein charmanter Rebell, der nicht durch Äußerliches oder Grobheiten dem allgemeingültigen Lebensbild trotzt, sondern subtil durch seine Taten darauf verweist, dass Liebe und ein Leben getragen von der Leidenschaft letztendlich glückbringender sind als Sicherheit und schnöder Mammon. Les-affaires, ein großes Stück Blauäugigkeit und Naivität lassen den Taugenichts in allerlei prekäre Situationen geraten. Das Schicksal beutelt ihn ordentlich durch, wirft ihn wie ein Staubkörnchen hin und her; er scheint dahin zu gehen, wohin ihn der Wind, leicht wie eine Feder, weht. Ein bisschen gleicht er Voltaires CANDIDE, und doch ist er unter einem glücklicheren Stern geboren, der ihm all das Leid dieser Welt erspart. Dementsprechend braucht er nicht wie CANDIDE dem Phoenix gleich der Asche entsteigen, sondern findet sein kleines Unglück schlimm genug, um ständig fortlaufen zu müssen. Andererseits hat er, was Friedrich Schlegel einmal – frei zitiert – als das einzige gottgleiche am Menschen betrachtete – den Müßiggang. Er lässt sich von Konventionen nicht überrumpeln und auch wenn’s ihm weh tut, dass er nicht dazugehört, so ist er doch ganz froh darüber, dass er tun und lassen kann, was er will. Und faul ist der Taugenichts ganz und gar nicht. Egon Friedell schrieb 1931: „Während Weber, auch in Not und Obskurität immer der Baron und Kavalier blieb, war Schubert zeitlebens der Eichendorffsche Taugenichts, der faule Hans vom Dorfe, der seine Freiheit gern mit Armut erkaufte. Und wie der „Taugenichts“ war er eigentlich gar nicht faul, sondern sehr fleißig, freilich ohne dass er es selbst wusste, indem er immerzu sang, ein halbes tausend Lieder!”

wenn Sie an dem Buch interessiert sind klicken Sie hier oder schreiben Sie an eh@akis.at