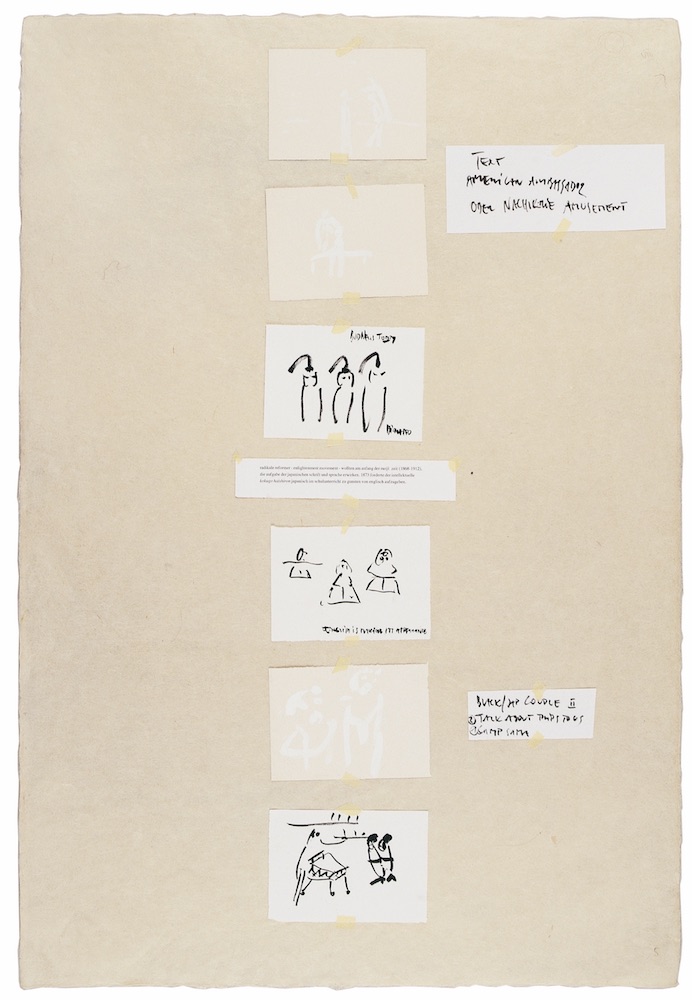

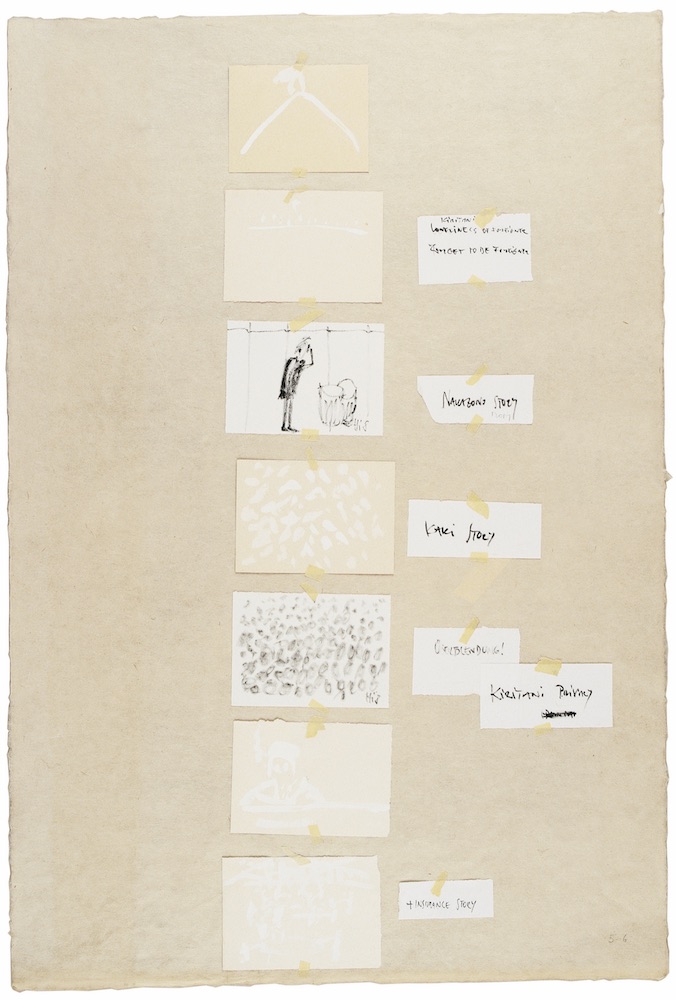

Tokyo / Vienna 2000, (film essay) 80 min

Once upon a time there was a fisherman who rowed his boat up a river. As he came upon a beautiful peach grove he discovered a village behind it that had been cut off the rest of civilization for many centuries. People there were peaceful and loved each other. The fisherman wanted to stay forever, but as he longed for his family he decided to go back home. On his way he left marks in order to be able to return. Soon he was tempted to go back – but as much as he searched – he never found paradise again.

appearances Yukika Kudo, Mishima Yukio, Kawabata Yasunari, Amamoto Hideyo, Imaii Toshimitsu a.o.

camera Norbert Artner, Edgar Honetschläger, Karl Neubert

editor Kurt Hennrich

line producer Karl Neubert / Tekipaki Studio

producers: Markus Fischer, Edgar Honetschläger

production company: Fischer Film

written and directed by Edgar Honetschläger

premiere at Rotterdam Film Festival

Original languages: Japanese and English

realised with the help of the Ministry of Culture Austria, ORF, Kulturland Oberösterreich, Japan Foundation

Please find a trailer and the film with German subtitles below:

EXCERPT version with english subtitles below

“I am happy if I can play around, people are sleeping. Meanwhile the traffic-jam. I wanna be like cockroach” says the girl while she rides on a boat through the canals of Tokyo located under three story highways. L + R is a a journey into past and present JAPAN, an essay narrated from A to Z by a young Japanese woman. She resists to see her world through the western directors eyes. time for her is – here and now. Digital directness and never shown PROPAGANDA FILM from the 1940’s (National Archives Washington) wave a colorful carpet of the love story (drama) between EAST and WEST, a man and a woman, L + R (election+erection).

L+R – a few notes

Japan’s occupation by the allied forces is one of the most remarkable chapters of world history. There has never been any other occupation where so much attention was paid to political and social reforms and there are few other societies that were so much altered and remodeled in such a short period of time.

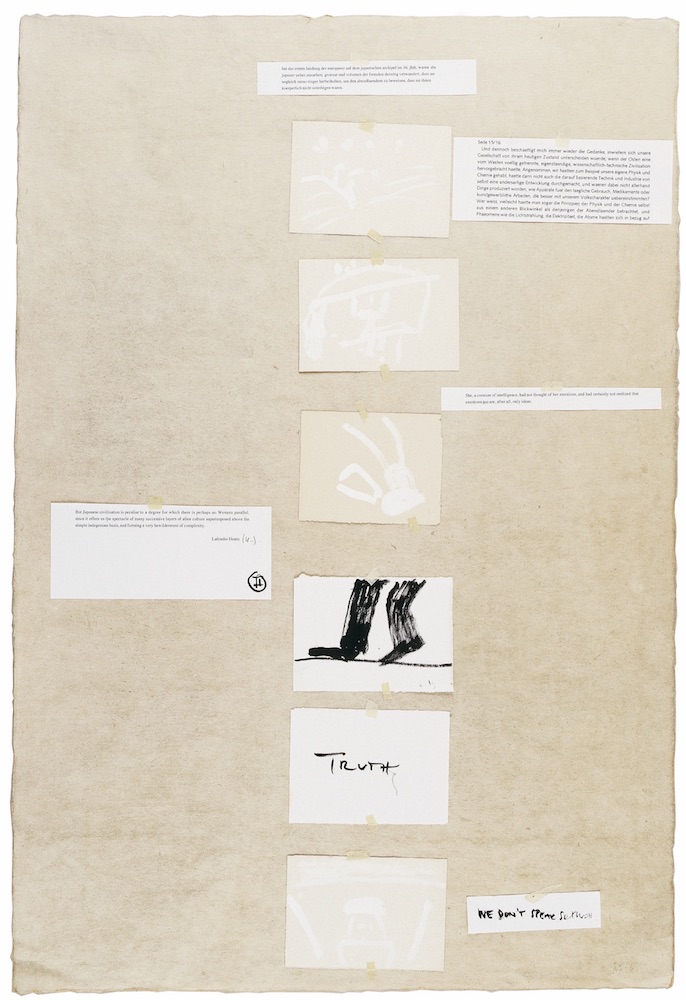

The Japanese (if such a generalization is admissible) have always tried to understand “others” but they do little to make themselves understandable, i.e. the common Western allegations on the utter collectivism, conformity and lack of individuality of “the Japanese” find a broad audience even in Japan itself. “Japan bashing” – a term coined by the Americans – as well as its consequences naturally express economic competition and even if all the pain resulting thereof is sometimes hard to bear, the defeated people may still retreat into the confirmation of stereoptypes. It is quite easy to adhere to the slogan “Nobody can understand us annyway” and as a matter of fact, neither hemisphere is really interested in transparency and approachability. Japan has succeeded in colonializing itself and thereby became colonialized more thoroughly than other Asian countries which were the direct victims of European colonization powers.

I subscribed to two Japanese newspapers for a longer period of time. Their reports focus, as elsewhere, principally on domestic affairs, then on the relationship between their own country and the USA. Asia as a trading partner, its politics and economic development is next on the agenda. Europe seems far away and if there are any reports on it at all, they mainly refer to extremes of various kinds, just as Europeans are usually confronted with similar reports on Japan. Judging from the image created thereby, I would – were I not European myself and therefore knew better – never ever want to live in a place of that much violence, radical right-wing rabble-rousers and war. However, the same conclusion holds vice versa as well.

In the second half of the 1990s, Europe suddenly started to focus on Japan with an intensity I find hard to understand. It almost seems as if the prospering America of the 50s and 60s with all its extremes and its stimulating and intellectual significance has now been superseded by Japan, the big unknown. Up to the 90s, for instance, there were – apart from publications dealing with the economic giant NIPPON and with the exception of the classical writers – hardly any German translations of Japanese literature. Today, Japan can be found all over the media, people like to boast about their relations to Japan and it has become trendy to know what’s going on there.

It was and still is my intention to create an access to Japan which – out of my personal experience and without any didactic or schoolmasterish ambitions – brings about an image that relativizes the reported and learned. My performance piece “97 – (13 + 1)” shown in documenta X, Kassel, Germany (curated by Catherine David) and the feature film “MILK” which had its premiere at the Berlinale 1998 are attempts to get an understanding of the West‘s perception of Japan. Furthermore they question the correctness of perception with consummate ease and try to observe the aforementioned extremes from different point of view.

L+R is another attempt to capture, seize and depict “the foreign and alien”. Trying to understand another culture through books or films usually brings about a rather dubious insight just as traveling abroad need not necessarily broaden one‘s personal horizon. We often encounter other cultures with preconceptions and when going abroad just search for confirmation of these preconceptions. Bernhard Waldenfels, a philosopher who devoted himself most exhaustively to the foreign and alien, writes that “the contingency of limited orders is the precondition for experiencing the alien, which – in a precise sense – means that something eludes the reach of order.” He refers to Husserl, who paradoxically defines the essence of the alien in the Cartesian Mediations, which go back to the Paris lectures of 1929, as “preservable accessibility in the original inaccessibility.”

L+R extends from “The Guest Who Stays” (Simmel) over to the typical tourist and finally to the specialist. By giving all of them a hearing I try to contrast and question their definitions of the foreign and alien and by doing so trying to stay away from the “explanatory” as much as a could. I did not want to bore my audience with the knowledge concerning Japan, which I had the time to accumulate throughout the last decade. For me it was important that the outcome would be as light and refreshing as possible and either cinematography or certain scenes give the “outsider” pleasure and joy.

For me the film is an essay in the sense that it does not try to convince anybody that the filmmakers angle is by any means objective. Yukika’s and my struggle with our so called “interracial relationship” and how we are trying to solve it gives the film the structure it might have otherwise totally lacked. As a matter of course, L+R reflects my personal situation as a wanderer between the cultures. However, I do not intend to “explain” the world from a cosmopolitan’s point of view, but rather show that the number of unsolved questions and enigmas constantly increases the more one exposes oneself to an alien culture. Humorously and without cynism, I tried to make different realities tangible and go into positions that are rather dubious to me. By questioning the position of the expatriate, as well as of all other travelers, wanderers or those who remain at home, my own existence also becomes an integral part of this caleidoscope where so much is left to be learned.

Most of the archival footage used, is taken from the national archives in Washington. Propaganda films from both sides of the Pacific. Some of the Japanese footage was used in the Tokyo trial after WW II and served to hang Japanese war criminals. I manipulated this footage strongly and turned its meaning upside down.

Three examples:

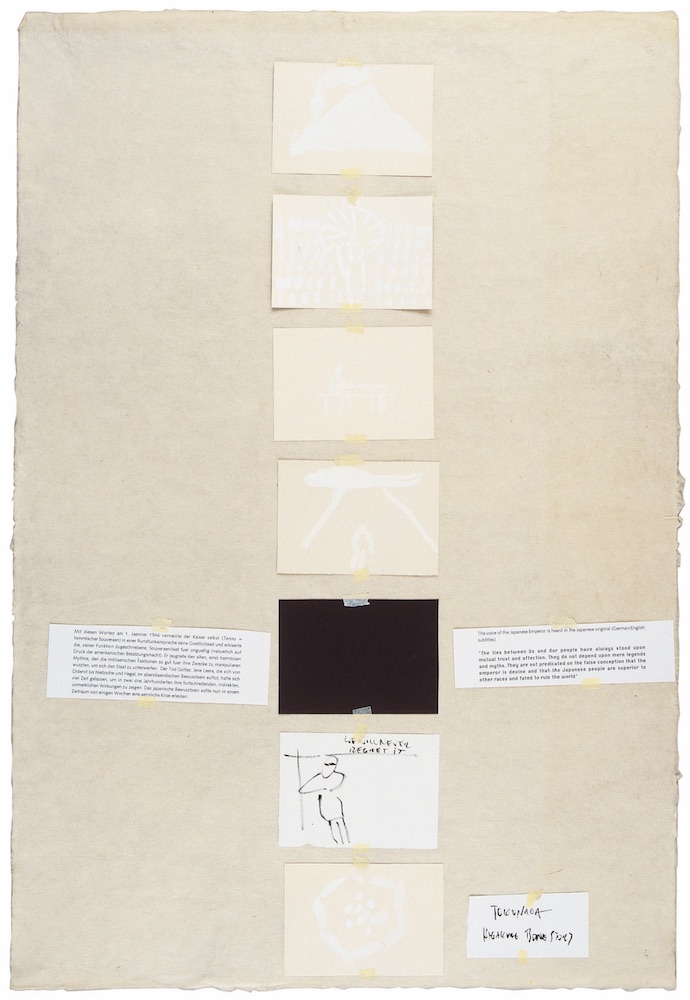

1) SPIRAL and VOICE — According to Maurice Pinguet (“La mort volontaire au Japon”) the emperor (Tenno = heavenly souvereign) spoke to his people in a radio speech aired on January 1, 1946, , telling them – upon pressure of the American occupation forces – that he was no longer considered to be a god. He denied the old, once harmless myth, which the military fractions exploited for their own purposes, in order to submit to the state. The death of God: The sense of emptiness which characterized the oczidental conscience from Diderot to Nietzsche and Hegel, took its time to show its continuous, indirect and imperceptible effect in two or three centuries. The Japanese were suddenly struck with a similar crisis and – since during post-war depression there wasn’t anymore time for further reflection – within a couple of weeks had to accept and internalize a situation which the Europeans took three centuries to put up with.

This material was not to be found because the Japanese deny – against everything I read from Western scholars – that the emperor himself ever went on air. According to NHK the emperors declaration was only printed in a newspaper. Therefore I had an actor fake the former emperors voice.

2) While a man sweeps the grounds of a temple the voice of the American ambasssador to Japan in the late 1930’s is to be heard : he states that the Japanese are not to be understood and that they are 2000 year out of date.

3) In a film by the Nazi director Dr. Arnold Fank, a Japanese playboy has a hard time to decide whether he is going to have Western drinks or Japanese Sake. The Americans took the footage and manipulated it by using an American overvoice. In the context I use the material the manipulation goes one step beyond.

L + R

Das „Paradies“ ist verloren. Die Kamera fährt im August 1945 vom Flugzeug aus über die zerbombte Geisterstadt Tokyo. Ein eisiger Wind bläst Winterkälte ins Bild von der Stadt, deren Leben erloschen scheint. Die Stimme aus dem Off bleibt ganz leise, als wagte sie aus Respekt vor den Toten nur zu flüstern: Sie erzählt von einem Fischer, der den Fluss hinauffuhr, an einen Pfirsichhain gelangte und dahinter ein Dorf entdeckte, wo Menschen in Frieden und Liebe zusammenlebten. Eine innere Stimme drängte ihn wieder fort, zurück zu den Seinen, doch kaum zu Hause, verspürte er nur ein Verlangen, wieder zurückzukehren. Der Weg dorthin, obwohl er ihn sorgsam mit Markierungen versehen hatte, war aber unauffindbar, der Ort der Harmonie für immer verloren.

Als der American Way of Life begann, über den japanischen Lebenstil hereinzubrechen, geriet etwas aus den Angeln, das den Weg zurück in einen früheren Zustand der inneren Ganzheit undenkbar macht. Wie ein unheilvoller Regen prasselten westliche Denkmuster auf die bis dahin noch immer in sich geschlossene Welt nieder, versickerten an manchen Stellen an der Oberfläche, schossen jedoch an anderen bis in die Tiefe, um alles Bestehende aufzulösen. Zwischen unerschütterlichen Fundamenten und widerstandslos aufgegebenen Alltagsdomänen entstand ein spannungsreiches Amalgam der beiden Kulturen.

Kontraste und Polaritäten sind das Wesen von L&R, das nicht eindeutig zu interpretierende Lachen Yukikas seine eigentliche Musik. Die Frage, ob es als naiv oder spöttisch zu verstehen ist, lässt der Film offen. Ihren westlichen Besucher begleitet die junge Japanerin durch die Kanäle Tokyos, um ihm eine Lektion zu erteilen. Mit einem entwaffnenden „You are asking me strange questions. Why I am doing this? – I don’t know. Europeans always need reason,“ zerlegt sie am Ende die letzten Versatzstücke des rationalen Konzeptes ihres Gegenübers, das mit ihrer Hilfe versucht, dem kulturellen Missverhältis auf die Spur zu kommen.

Zu Beginn gehen Yukika und ihr Gegenpart aus dem Westen aneinander vorbei, in der Mitte des Films nehmen sie kurz voneinander Notiz, auch wenn sie zu ihm aufschauen muss, am Ende schreiten sie im Gleichklang einen langen Gang ab. Die Sphären von Intuition und Intention sind zwar aneinandergeraten, haben aber schließlich die eingleisige Sicht auf die Dinge in beide Richtungen geöffnet.

Lachen und Tränen, Märchen und Ratio, ein Mann und eine Frau, Westen und Osten, ein Wechselspiel der Pole spannt den Bogen in L + R, das in der kleinsten Einheit, in der sich bereits die Unvereinbarkeit der beiden Welten ausmachen lässt, seinen Ausgang nimmt: das Buchstabenpaar L&R, das für viele Japaner eine unüberwindliche phonetische Hürde darstellt, ist gleichsam die Reduktion des Kontrastes zwischen der zielgerichtet im Vordergrund agierenden Denkweise des Westens und der gelassen aus dem Hintergrund wirkenden des Ostens.

L + R ist eine Komposition aus poetischer Bildersprache und asiatischer Dichtung, noch nie publiziertem Archivmaterial und Momentaufnahmen aus Tokyos Alltag, erfasst von einer statischen, als stiller Beobachter fungierenden Kamera. Sie unterstreicht zunächst die Unkenntnis der beiden Sphären voneinander und das Unverständnis, das ihrer Annäherung entgegensteht. Nach und nach lässt der Film ein vielschichtiges Portrait einer fremden Welt entstehen, für die die Amerikaner im spontanen Interview nur Attribute wie sexy, teuer, verrückt, oder schlichtweg sehr anders finden. „For Americans“,erklärt eine Amerikanerin gleichsam entschuldigend an anderer Stelle, „the rest of the planet is just an idea“.

Diese saloppe Wahrnehmung des Fremden bietet gleichzeitig auch die Chance zwischen kultureller Selbstaufgabe und Identitätsbehauptung Raum zu schaffen. Die Kamera in L + R stöbert diese Schlupflöcher auf und gewährt berührende wie unterhaltsame Einblicke in selbständige Mikrokosmen. Die Möglichkeiten, sich Freiräume zu schaffen, entstehen genau dort, wo der westliche Beobachter das Ende des Individualismus vermutet. Lakonisch merkt Yukika an „There are many people, so I can hide very well“ eine Schlussfolgerung, die zwei Pforten öffnet – untergehen in der Masse, aber auch unbeobachtet dort sein Eigenes tun, wo es der Umwelt unmöglich ist, alles im Auge zu bewahren.

Keine Sequenz stellt eindrucksvoller die Konfliktsituation dar, die L + R mit so dichten Bildern herausarbeitet als jene, wo sich einige Karpfen gierig auf ein halb abgenagtes Fischskelett stürzen, das ihnen zum Fraß vorgeworfen wird. Ist es der Westen, der sich auf die schon halb zerbrökelte japanische Kultur stürzt, um auch noch die Reste zu verschlingen, oder sind es die Japaner, die scheinbar blind und bedachtlos alles annehmen und verinnerlichen, was vom übermächtigen Nachbarn kommt?

In einem Punkt scheiden sich jedenfalls bei noch so williger Bereitschaft zur Unterwerfung, bei noch so aggressiven kulturellen Vereinnahmungssstrategien die Geister: im Umgang mit der Zeit. „Time gives me a lot of pleasure“, erklärt Yukika, „for me it is a present from the universe“. Die Ursache für die Rastlosigkeit der Menschen im Westen vermutet der Schriftsteller Junichiro Tanizaki darin, dass diese ständig bemüht sind, der Dunkelheit zu entkommen. Menschen in der östlichen Sphäre hingegen lieben die Dunkelheit und fühlen sich geborgen in der Welt der Schatten.

L+R ist eine spannende Erkundungsreise durch die Halbschatten zweier Kulturen, verschwommene Grautöne nehmen Konturen an in dieser sachten und sensiblen „Märchen“, das die Verehrer der Dunkelheit in ein in vielen Facetten schimmerndes Licht taucht.

KARIN SCHIEFER